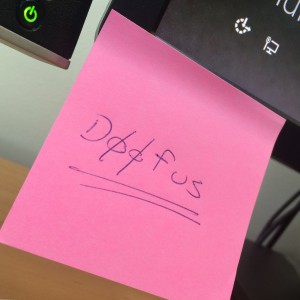

Time and time again, we see calls from security experts for complex passwords. Make sure your password includes lower case letters, upper case letters (how xenoglossophobic!), numerals, punctuation, star signs, and emoji. It must be no less than 23 characters long and not use the same character twice. Change your password every 60 days, every 30 days, every half hour. Don’t use the same password again this year, or next year, or for the next 6 galactic years. Never write your password down. Especially not on a post-it on your monitor. Or under your keyboard.

The Golden Password Rules

And it’s all wrong. There are just two rules you need to remember, as an Internet password user:

- Never use the same password in two places. Like, if you have a Yahoo account and a Google account, don’t let them share the same password. They’d be offended if they knew you did anyway.

- Make sure your password isn’t “guessable”, like your pet’s name, or your middle name. Or anyone’s middle name. Or “password”. Or anything like that. But “correct horse battery staple” is probably ok, or it was until xkcd published that cartoon.

It’s all wrong because all that complexity jazz is just part of an arms race in the brute force or dictionary attack password cracking game.

Say what? So a brute force attack is, in its simplest form, a computer — or hundreds of computers — trying everything single password combination they can think of, against your puny little password. And trust me when I say a computer can think of more passwords than you can. Have you ever played Scrabble against a computer?

Brute force attacks on Internet passwords are only effective on well designed sites when that site has already been compromised. At which point who cares if they know your password to that site (because rule 1, remember): they also know everything else that site has recorded about you. And anyway you can just change that password. No problem (for you; the site owners have a big problem).

Now, if you are unlucky enough to be targeted, then complex passwords are not going to save you, because the attackers will find another way to get your data without needing to brute force your Google Apps password. We’ve seen this demonstrated time and time again. And if you are not being targeted, then you can only be a victim of random, drive-by style password attacks. And if you followed rule 2, then random, drive-by style password attacks still won’t get you, because the site owner has followed basic security principles to prevent this. And if the site owner has not followed basic security principles, then you are stuffed anyway, and password complexity still doesn’t matter.

In fact, complex passwords and cycling regimes actually hurt password security. The first thing that happens is that users, forced to change passwords regularly, can no longer remember any passwords. So they start to use easier to guess passwords. And eventually, their passwords all end up being some variation of “password123!”.

The Bearers of Responsibility

The people who really have to do the hard yards are the security experts, software developers, and the site owners. They are the keepers of the password databases and bear a heavy burden for the rest of us. Some suggestions, by no means comprehensive, for this to-be-pitied crew:

- Thwart dictionary attacks on Internet-facing password entry. That is, throttle connection attempts, delay for 15 seconds after 10 attempts, require 2nd level authentication after failed attempts, that kind of thing. These solutions are well documented.

- Control access to your password database (duh). Remember, in the good ol’ days of Unix, password were stored in /etc/passwd, which was world readable and so the enterprising young hacker could just copy the file and try and crack it in their own good time elsewhere. So keep other people’s dirty paws off your (hashed) password database.

- Don’t ever display passwords in plain text. No “here is your password” emails. Not even for registration. That has to be a one time token. Your password database is hashed, right? Not ROT13?

- Notify a user if someone tries to access their account multiple times. Give them the power to fret and stress.

- If your site gets hacked, tell your users as soon as you possibly can, and reset your password database. Mind you, they’ll just have to change their password for your site because they’ve been following rule 1 above, right? Oh, and don’t be too ashamed to tell anyone. It happens to all the best site owners and there’s nothing worse than covering it up.

The Flaw in My Rant

Still, my rant has a problem. It’s to do with Rule 1: A separate password for every site. But just how many sites do I have accounts for? Right now? 402 sites.

Yikes.

How do I manage that? How can I remember passwords for 402 sites? I can’t! So I put them into a database, of course. Managed by a password app such as KeePass or 1Password or Password Safe. Ironically, as soon as I use a password manager, I no longer have to make up passwords, and they actually end up being random strings of letters, numbers and symbols. Which keeps those old-fashioned password nazis happy too.

Personally, I keep a few high-value passwords out of the password database (think Internet Banking) and memorise them instead.

Of course, my password safe itself has just a single password to be cracked. And because I (the naive end user) store this database on my computer, it’s probably easy enough to steal once I click on that dodgy link on that site… At which point, our black hat password cracker can roll out their full armada of brute force password cracking flying robots to get into my password database. So perhaps you still need that complex password to secure your password database?

What do you think?

Note: Roger Grimes stole my thunder.

I both agree and disagree. I disagree with the ‘use a different password for every single site’. I do agree that most of the password requirements are goofy, and don’t help much (yes, password123! or TomBradSarah2014)

As someone who sees brute force attacks constantly, I don’t get the luxury of blocking every IP after three attempts, and so forth (The systems do not lend themselves to that without buying not-cheap third party tools). On the other hand, the same systems don’t let me have a password such as “fourscoreandtwentyyearsagoourforefathersbroughtforthupon” – which is easy to remember, but as for a dictionary attack? Not likely – especially if you leave one of the words out.

What I recommend to customers is a different approach. I tell them to have two or three passwords, and use them for all of their sites – but then keep a spreadsheet with the sites they use, their usernames, and the emails associated with them. I _then_ tell them to, at least once a year, and preferably twice, take a few hours to just run through the sites and change the passwords. Those passwords are never put in the computer, but rather kept written down separately from the spreadsheet. These people will _not_ use password managers and many of the ‘managers’ are thinly disguised adware anyway, so I try to mitigate the disaster potential.

Yes, the stolen hash tables can be broken, but with luck, by the time they’ve managed to break the encryption, you’ve already changed the password for those sites without some scary email showing up saying “Sorry, we had a break-in 9 months ago, and we finally decided it was worth telling you so you can change your passwords, email, credit cards, and move to a banana republic. The Attorney General’s office hitting us with a subpoena didn’t have anything to do with it.”

My personal local passwords? All over 23 characters long. I’m a touch typer, it’s no big deal. (and no, it’s not every letter of the alphabet other than C, Q, and W, because I just don’t like them)

Thanks for reading and your thoughts, Troy — you make some good points regarding brute force protections and password managers. I get the idea of the spreadsheet approach, but don’t think it’d work for me — I am not organised enough to make that feasible 🙂