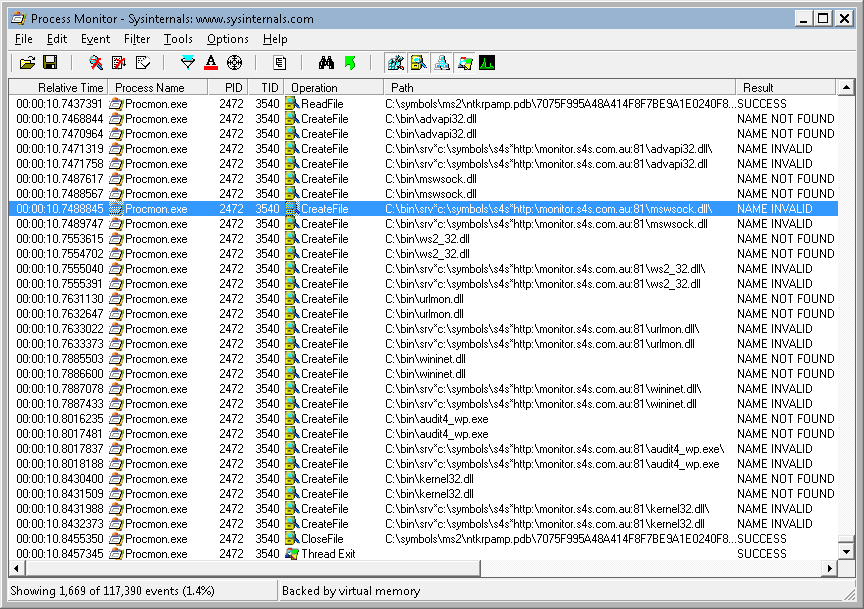

Today I’ve got a process on my machine that is supposed to be exiting, but it has hung. Let’s load it up in Windbg and find what’s up. The program in question was built in Delphi XE2, and symbols were generated by our internal tds2dbg tool (but there are other tools online which create similar .dbg files). As usual, I am writing this up for my own benefit as much as anyone else’s, but if I put it on my blog, it forces me to put in enough detail that even I can understand it when I come back to it!

Looking at the main thread, we can see unit finalizations are currently being called, but the specific unit finalization section and functions which are being called are not immediately visible in the call stack, between InterlockedCompareExchange and FinalizeUnits:

0:000> kb ChildEBP RetAddr Args to Child 0018ff3c 0040908c 0018ff78 0040909a 0018ff5c audit4_patient!System.Sysutils.InterlockedCompareExchange+0x5 [C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD Studio\9.0\source\rtl\sys\InterlockedAPIs.inc @ 23] 0018ff5c 004094b2 0018ff88 00000000 00000000 audit4_patient!System.FinalizeUnits+0x40 [C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD Studio\9.0\source\rtl\sys\System.pas @ 17473] 0018ff88 74b7336a 7efde000 0018ffd4 76f99f72 audit4_patient!System..Halt0+0xa2 [C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD Studio\9.0\source\rtl\sys\System.pas @ 18599] 0018ff94 76f99f72 7efde000 35648d3c 00000000 kernel32!BaseThreadInitThunk+0xe 0018ffd4 76f99f45 01a5216c 7efde000 00000000 ntdll!__RtlUserThreadStart+0x70 0018ffec 00000000 01a5216c 7efde000 00000000 ntdll!_RtlUserThreadStart+0x1b

So, the simplest way to find out where we were was to step out of the InterlockedCompareExchange call. I found myself in System.SysUtils.DoneMonitorSupport (specifically, the CleanEventList subprocedure):

0:000> p eax=01a8ee70 ebx=01a8ee70 ecx=01a8ee70 edx=00000001 esi=00000020 edi=01a26e80 eip=0042dcb1 esp=0018ff20 ebp=0018ff3c iopl=0 nv up ei pl nz na po nc cs=0023 ss=002b ds=002b es=002b fs=0053 gs=002b efl=00200202 audit4_patient!CleanEventList+0xd: 0042dcb1 33c9 xor ecx,ecx

After a little more spelunking, and a review of the Delphi source around this function, I found that this was a part of the System.TMonitor support. Specifically, there was a locked TMonitor somewhere that had not been destroyed. I stepped through a loop that was spinning, waiting for the object to be unlocked so its handle could be destroyed, and found a reference to the data in question here:

0:000> p eax=00000001 ebx=01a8ee70 ecx=01a8ee70 edx=00000001 esi=00000020 edi=01a26e80 eip=0042dcaf esp=0018ff20 ebp=0018ff3c iopl=0 nv up ei pl nz na po nc cs=0023 ss=002b ds=002b es=002b fs=0053 gs=002b efl=00200202 audit4_patient!CleanEventList+0xb: 0042dcaf 8bc3 mov eax,ebx

Looking at the record pointed to by ebx, we had a reference to an event handle handy:

0:000> dd ebx L2

01a8ee70 00000001 00000928

TSyncEventItem = record

Lock: Integer;

Event: Pointer;

end;

Although Event is a Pointer, internally it’s just cast from an event handle. So I guess that we can probably find another reference to that handle somewhere in memory, corresponding to a TMonitor record:

TMonitor = record

strict private

// ... snip ...

var

FLockCount: Integer;

FRecursionCount: Integer;

FOwningThread: TThreadID;

FLockEvent: Pointer;

FSpinCount: Integer;

FWaitQueue: PWaitingThread;

FQueueLock: TSpinLock;

And if we search for that event handle:

0:000> s -[w]d 00400000 L?F000000 00000928 01a8ee74 00000928 00000000 0000092c 00000000 (.......,....... 07649334 00000928 002c0127 0012ccb6 0000002e (...'.,......... 0764aa14 00000928 01200125 004b8472 000037ce (...%. .r.K..7.. 07651e24 00000928 05f60125 01101abc 00000e86 (...%........... 08a47544 00000928 00000000 00000000 00000000 (...............

Now one of these should correspond to a TMonitor record. The first entry (01a8ee74) is just part of our TSyncEventItem record, and the next three don’t make sense given that the FSpinCount (the next value in the memory dump) would be invalid. So let’s look at the last one. Counting quickly on all my fingers and toes, I establish that that makes 08a47538 the start of the TMonitor record. And… so we search for a pointer to that.

0:000> s -[w]d 00400000 L?F5687000 08a47538 076b1d24 08a47538 08aa3e40 076b1db1 0122fe50 8u..@>....k.P.".

Just one! But here it gets a little tricky, because the PMonitor pointer is in a ‘hidden’ field at the end of the object. So we need to locate the start of the object.

0:000> dd 076b1d00 076b1d00 0122fe50 00000000 00000000 076b1df1 076b1d10 0122fe50 00000000 00000000 076b0ce0 076b1d20 004015c8 08a47538 08aa3e40 076b1db1 076b1d30 0122fe50 00000000 00000000 076b1d51 ... snip ...

I’m just stabbing in the dark here, but that 004015c8 that’s just four bytes back smells suspiciously like an object class pointer. Let’s see:

0:000> da poi(4015c8-38)+1 004016d7 "TObject&"

Ta da! That all fits. A TObject has no data members, so the next 4 bytes should be the TMonitor (search for hfMonitorOffset in the Delphi source to learn more). So we have a TObject being used as a TMonitor lock reference. (Learn about that poi(address-38)+1 magic). But what other naughty object is hanging about, using this TObject as its lock?

0:000> s -[w]d 00400000 L?F5687000 076b1d20 098194b0 076b1d20 00000000 00000000 09819449 .k.........I...

Just one. Let’s trawl back in memory just a little bit and have a look at this one.

0:000> dd 09819480 09819480 00f0f0f0 00ffffff 00000000 09819641 09819490 00447b7c 00000000 00000000 00000000 098194a0 00000000 098150c0 00448338 098195c8 098194b0 076b1d20 00000000 00000000 09819449 ... snip ... 0:000> da poi(00448338-38)+1 004483c0 "TThreadList&"

And what does a TThreadList look like?

TThreadList = class

private

FList: TList;

FLock: TObject;

FDuplicates: TDuplicates;

Yes, that definitely looks hopeful! That FLock is pointing to our lock TObject… I believe that’s called a Quality Match.

This is still a little bit too generic for me, though. TThreadList is a standard Delphi class used by the bucketload. Let’s try and identify who is using this list and leaving it lying about. First, we’ll quickly have a look at that TThreadList.FList to see if it has anything of interest — that’s the first data member in the object == object+4.

0:000> dd poi(098194ac) 098195c8 00447b7c 00000000 00000000 00000000 ... snip ... 0:000> da poi(447b7c-38)+1 00447cad "TList'"

Yep, it’s a TList. Just making sure. It’s empty, what a shame (TList.FCount is the second data member in the object == 00000000, as is the list pointer itself).

So how else can we find the usage of that TThreadList? Is it TThreadList referenced anywhere then? Break out the search tool again!

0:000> s -[w]d 00400000 L?F5687000 098194a8 076d3410 098194a8 00000000 09819580 00000000 ................

Yes. Just once, again. Again, we scroll back in memory to find the base of that object.

0:000> dd 076d33c0 076d33c0 08abfe60 00000000 00000000 076d4c39 076d33d0 01616964 0000091c 00001850 00000100 076d33e0 00000001 00000000 00000000 00000000 076d33f0 076d33d0 00000000 01616d38 076d33d0 076d3400 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 076d3410 098194a8 00000000 09819580 00000000 076d3420 00000000 076d2ea9 0075e518 00000000 076d3430 00401ecc 00000000 00000000 00000000

There was a false positive at 076d33f8, but then magic happened at 076d33d0:

0:000> da poi(01616964-38)+1 016169e8 "TAnatomyDiagramTileLoaderThread&"

Wow! Something real! Let’s dissect this a bit. Looking at the definition of TThread, we have the following data:

076d33d0 01616964 class pointer TAnatomyDiagramTileLoaderThread 076d33d4 0000091c TThread.FHandle 076d33d8 00001850 TThread.FThreadID 076d33dc 00000100 TThread.FCreateSuspended, .FTerminated, .FSuspended, .FFreeOnTerminate (watch that endianness!) 076d33e0 00000001 TThread.FFinished 076d33e4 00000000 TThread.FReturnValue 076d33e8 00000000 TThread.FOnTerminate.Code 076d33ec 00000000 TThread.FOnTerminate.Data 076d33f0 076d33d0 TThread.FSynchronize.TThread (= Self) 076d33f4 00000000 padding 076d33f8 01616d38 TThread.FSynchronize.FMethod.Code (= last Synchronize target method) 076d33fc 076d33d0 TThread.FSynchronize.FMethod.Data (= Self) 076d3400 00000000 TThread.FSynchronize.FProcedure 076d3404 00000000 TThread.FSynchronize.FProcedure 076d3408 00000000 TThread.FFatalException 076d340c 00000000 TThread.FExternalThread

Then, into TAnatomyDiagramTileLoaderThread:

076d3410 098194a8 TAnatomyDiagramTileLoaderThread.FTiles: TThreadList

So… we can tell that the thread has exited (FFinished == 1), and verify that by looking at running threads, looking for thread id 1850:

0:000> ~ . 0 Id: 1c98.1408 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7efdd000 Unfrozen 1 Id: 1c98.16c8 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7efda000 Unfrozen 2 Id: 1c98.11a0 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7ee1c000 Unfrozen 3 Id: 1c98.1bbc Suspend: 1 Teb: 7ee19000 Unfrozen 4 Id: 1c98.10dc Suspend: 1 Teb: 7ee04000 Unfrozen 5 Id: 1c98.12f0 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7edfb000 Unfrozen 6 Id: 1c98.1d38 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7efaf000 Unfrozen 7 Id: 1c98.1770 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7edec000 Unfrozen 8 Id: 1c98.1044 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7ede3000 Unfrozen 9 Id: 1c98.bf4 Suspend: 1 Teb: 7ede0000 Unfrozen 10 Id: 1c98.b3c Suspend: 1 Teb: 7efd7000 Unfrozen

Furthermore, the handle is invalid:

0:000> !handle 91c Could not duplicate handle 91c, error 6

That suggests that the object has already been destroyed. But that the TThreadList hasn’t.

And sure enough, when I looked at the destructor for TAnatomyDiagramTileLoadThread, we clear the TThreadList, but we never free it!

Now, another way we could have caught this was to turn on leak detection. But leak detection is not always perfect, especially when you get some libraries that *cough* have a lot of false positives. And of course while we could have switched on heap leak detection, that involves rebuilding and restarting the process and losing the context along the way, with no guarantee we’ll be able to reproduce it again!

While this approach does feel a little tedious, and we did have some luck in this instance with freed objects not being overwritten, and the values we were searching for being relatively unique, it does nevertheless feel pretty deterministic, which must be better than the old “try-it-and-hope” debugging technique.